Since 1985, film has played a central role in developing boundary language concepts and analytical techniques. In particular, the filmic “fourth wall” has linked to architecture’s concept of the section and orthogonal projection, where the inside–turned–outside logic is a direct example of Lacanian extimity. In film reviews (“The Strange Love of Dystopia,” Art Papers and “The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock” (Journal of Architectural Education) and in conferences (David Lynch Symposium), the concept of liminality has bridged the gap between contemporary architectural practices and ethnography of the uncanny.

Hobson’s Choice. In conversation with George Bartlett, a Lacanian scholar working in Cairo, I proposed a research project involving the film “Hobson’s Choice.” The idea would be to use this charming 1954 film about the ambitions of the “homely daughter” of a successful boot-maker in Manchester, England. Unlike her younger and prettier sisters, she is demeaned by her blustery father (Henry Hobson, played by Charles Laughton). The title of the film, of course, invites comparisons to Lacan’s idea of the “forced choice,” the appearance of freedom when in fact there is only one option. This goes to the larger issue of the issue of freedom in the first place. For Lacan, our least free moments are those when it seems we have total freedom. It is there that we use fantasy constructs to confirm our VOWS to the Other, so to speak. Within the fantasy, components of the vow (cf. responsibility, social obligations, personal destiny) lay the ground for instrumental convergence, a process whereby “we get what we asked for” but in an inverted form.

This is an experimental adventure. First, a detailed précis of the film’s story is presented to ChatGPT, who then constructs several summaries. These will inspire a direction that, once chosen, will determine the style of the essay and its theoretical ambitions. Second, Chat organized an open-lattice outline. Editor and author will discuss possibilities and determine the focus of of the final essay.

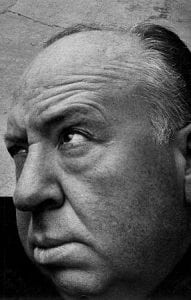

The Wrong House (book review). To say that Alfred Hitchcock designed his sets to tell and not just support stories would be an understatement. Beginning as a set designer himself, this famous thriller auteur redefined the idea of filmic space. In his best-known one-set films (Rope, Rear Window, Dial ‘M’ for Murder), spaces are locked and unlocked, sometimes by hidden keys, sometimes by the glances and gestures. But, even in other films, much of the story takes place within single buildings that trap or challenge the subject. In Rebecca, the young second Mrs. De Winter (whose own name we never learn) finds herself in what Jacques Lacan would call a “treasury of signifiers”; the house becomes the tomb or, worse, the fragmented corpse of the not-totally-dead first wife. Similarly, the mission tower in Vertigo, the modernist Vandamm house, the urban courtyard in Rear Window, and other architectural constructs are not simply backdrops for drama. They are the body for the soul a filmic imagination that moves beyond the story’s diegesis to speak directly to audience anxiety.

The Wrong House (book review). To say that Alfred Hitchcock designed his sets to tell and not just support stories would be an understatement. Beginning as a set designer himself, this famous thriller auteur redefined the idea of filmic space. In his best-known one-set films (Rope, Rear Window, Dial ‘M’ for Murder), spaces are locked and unlocked, sometimes by hidden keys, sometimes by the glances and gestures. But, even in other films, much of the story takes place within single buildings that trap or challenge the subject. In Rebecca, the young second Mrs. De Winter (whose own name we never learn) finds herself in what Jacques Lacan would call a “treasury of signifiers”; the house becomes the tomb or, worse, the fragmented corpse of the not-totally-dead first wife. Similarly, the mission tower in Vertigo, the modernist Vandamm house, the urban courtyard in Rear Window, and other architectural constructs are not simply backdrops for drama. They are the body for the soul a filmic imagination that moves beyond the story’s diegesis to speak directly to audience anxiety.

Architecture and Its Doubles: Real Travel, Enthymeme, and Antonomasia in the Sutured Topography of Mulholland Drive and North by Northwest

Architecture and Its Doubles: Real Travel, Enthymeme, and Antonomasia in the Sutured Topography of Mulholland Drive and North by Northwest

The landscape phenomenon is most often translated as the “visible landscape,” privileging sight’s ability to take in vast ranges of data and compress them into visual signatures summarizing ways of life, physical and geological resources, and historical processes. The Berkeley geographer Carl Sauer (1889- 1975) compared vision’s powers of quick synthesis to the landscape’s complex amalgamation of diverse factors, nearly sealing the pact between visibility and landscape. “Topography,” however, creates a small but significant proviso that, like a hidden clause in a contract, threatens to unravel this sweet deal between landscape and visibility. Although topography supports the ways in which the landscape can be seen, by opening or closing up vistas, creating countless occasions for “scenes,” topography is a surface, a form, that ultimately yields more to touch than to sight. The case for landscape’s tangibility is not about materiality per se but rather argues for the “synesthetic” potential of movement across the landscape’s surface as a humanistic rather than a mechanical motion. Real travel is balanced between the totalizing intentionality of an errand, which ignores the landscape and cannot even stop to ask for directions, and the failure of intentionality that leads to idle wandering or getting lost or stuck.