There are stories that, while about actual events, do not fall into any academic category. The ghost story entertains more than it instructs, but its entertainment value at some point converts into spooky prophecy. The Romans had multiple categories of warnings: omens of course but also ostentum, prodigium, miraculum, and the interesting class, monstrum, where composite bodies tell the mystery of changing seasons (the lion head and serpent tail). Ghost stories themselves have the monstrous desire to “combine that which ought not to be combined,” so the main feeling from a ghost story comes out of the sheer spookiness of transgression. In projective geometry even the simplest versions, such as the Möbius band, have this sense, that the “should-not-meet” has met, and the ghost story is a narrative form of cross-cap or Klein bottle, with the reader as the poor ant who, wandering along the surface without crossing any barriers, suddenly finds itself outside. Or inside.

All of these stories are true, but in some cases the truest parts had to be left out, for reasons spookier still.

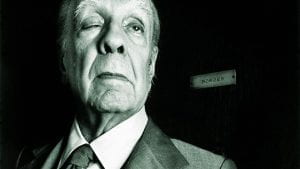

My Stupid Encounter with Borges

My friend Robert Lima, poet and Enxebre Orden da Vieira in Spain and dubbed Knight Commander in the Order of Queen Isabel of Spain by King Juan Carlos I, had invited the famous Argentine short-story writer and poet, Jorge Luis Borges, to my university in the 1985. Borges died the year after. Borges, as a recent book about his travel to Scotland has noted, had aspects of a “boisterous two-year-old” (Jay Parini, Borges and Me: An Encounter, 2021). It was as if his blindness empowered him to lead others into risky adventures. His lecture was, as expected, buoyant, and afterwards Lima offered to introduce me to Borges. I was terrified and excited — I had so many questions! — but when I shook the hand of this master, all I could think of to say was “Nice to meet you … I admire your work.”

My friend Robert Lima, poet and Enxebre Orden da Vieira in Spain and dubbed Knight Commander in the Order of Queen Isabel of Spain by King Juan Carlos I, had invited the famous Argentine short-story writer and poet, Jorge Luis Borges, to my university in the 1985. Borges died the year after. Borges, as a recent book about his travel to Scotland has noted, had aspects of a “boisterous two-year-old” (Jay Parini, Borges and Me: An Encounter, 2021). It was as if his blindness empowered him to lead others into risky adventures. His lecture was, as expected, buoyant, and afterwards Lima offered to introduce me to Borges. I was terrified and excited — I had so many questions! — but when I shook the hand of this master, all I could think of to say was “Nice to meet you … I admire your work.”

I had momentarily blanked out the fact that my life had been changed by reading, in one Borges story in particular, something that had happened to me personally well before I had ever heard about Borges. This proved to me that fiction can still outclass reality by giving us back what we experience, but “on a platter.” My experience wasn’t the kind of anecdotal irony to be found in “Pierre Menard, True Author of Don Quixote” or “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” where a hypothetical situation provokes the reader to add more outcomes than the writer provides, while still crediting the story. This was an encounter with the (Lacanian) impossible-Real, where “the facts of the case” burst the wrappings of the dream that contained it.

Borges’ story in this case was “The Aleph.” It was Lima’s favorite, since Lima himself was a bit of a magus and had traveled to conferences on magic (Brazil, I think) where, on stage, he had held hands with the other lecturers and felt a distinct jolt of electricity. In the Borges story, the owner of a house in Buenos Ares shares a secret about the space beneath the cellar stairs with his cousin, who is the point-of-view narrator. When the cousin is persuaded to lie on his back and stare into the darkness beneath the treads, a point of light grows bright and transforms itself, from a figure into a ground, a hole in the space in which it has previously floated as a small sphere. Through the hole the cousin sees into both the past and the future, amazing scenes compacting, with the impossible precision known to those who suffer from neurological hallucinations, time, space, and detail.

My aleph encounter had happened years before I met or even knew about Borges. Note that this order — the “magic event” coming before the “explanation” — is what makes the predictive dream so convincing, just as the posterior logic of déjà vu holds us in the reverse grip. In college, I frequently visited my girlfriend, now wife, and a group of friends, mostly artists living in the kind of decrepit neighborhood where houses past their primes have been rented to students but occasionally bought by faculty with renovation skills. Such was the one-story, classic Carolina “gunshot” house, so-called because, from the front door to the small back porch, rooms were enfiladed without a hallway. Thanks to a site that sloped down from the street, Andy, a painter on the faculty at the university, could now work at home, presumably taking the advantage of a private studio to drink, smoke, and all of the other things that tend to fuel the production of art.

To celebrate the final stages of construction, Andy had a party, and my Turkish friend, who lived across the street in a more noble structure, got me invited. I remember the party but I remember it in two parts, the part where I drank wine and talked to a lot of people I’d never met, and the dream I had shortly afterwards, where something that “shouldn’t have happened” happened. In the dream party, I was leaning against the back wall that faced the open yard, which Andy had enlarged to get more light into the otherwise dank room. The room was, by this time, as dark as the night outside, and when I saw the small light I thought it was a decorative party-light, odd because there was only one of them, and seemingly detached from any electrical wire or string to suspend it.

In fact the light was floating, and the more I looked at it, the more its edges expanded, to the size of a ping-pong ball, but at the same time it was cutting through the space that should have been behind it, as if the space of Andy’s basement was 2-d and there was a circular tear that gave a view of a space beyond. Within or behind this small sphere, things moved across the field rapidly, even more convincing me that we were only thinking we were in a full three-dimensional space, that this was disproven by seeing through this hole.

In dreams you say stupid things, just like my encounter with the non-dreamed Borges, but in the dream the stupid thing is the ticket to the dream’s punch-line, whereas in my encounter with the Argentine master of the short story, it was a cue for me to slip away as quietly as possible. In the dream, the girl next to me seemed unexcited about this tiny sphere, even though she was staring at it as intently as I. Was she Andy’s student? A friend? A girlfriend? I turned to her, not wanting to show how terrified I was, which in the dream would have been “un-cool.” What is THAT, I asked. “Oh, that? That’s the Eye of Allah. Andy keeps it for a pet.”

Dreams, my dreams at least, have a way of reducing the magisterial to the mawkish, either to discredit the dream as having any value or as an act of self-deprecation, as if to say “You can’t even have a decent dream experience!” That was my feeling, at least, that I had been shown something truly revolutionary but then told it wasn’t for me to understand, as if my dream-production team was looking to move on to a new and more sophisticated client.

What was I expecting Borges to say? What was I going to say? That I had dreamed of a magical object before reading his story? That although his story was fiction, my dream was “real”? Possibly forgetting to tell Borges was one of those demons that Socrates had, which only worked to prevent him from saying something idiotic. Or, maybe Borges the two-year-old would have excitedly told me that the story was about something that had actually happened to him, or that he had dreamed it with the same sense of discovery I had had. I was not to have a second chance, Borges died the next year. Lima is dying this year.

The Hilarious Funeral

This is a true story, not a dream or made-up fiction. True stories include dreams and made-up fictions, but only because they are obliged to include “everything under the sun.” At that delicate balance between the time when one’s grandparents are still living or just freshly dead and the period when one is an “adult orphan,” funerals are the same as weddings. The Irish joke gives the mathematics of the difference between them, “one less drunk.” This one was for my wife’s aunt, whose love of cigarettes came to one of the predictable conclusions, with the unpredictable fact of being in Virginia rather than Pennsylvania or New Jersey, the family’s preferred domains.

There were enough grandchildren by this time to provide the funeral with heartfelt testimonies, so the event went well enough. The crowd left the rural chapel, which could have not have possibly been Catholic in this wooded backland of the south, to prepare their cars for the procession to the cemetery some five miles distant. The gravel parking lot was large and circular, so the impression was that of a ring of modernized covered wagons, hitched up and ready for the trek west across Nebraska. Thanks to my wife’s connections, we were to be the “lead car,” carrying the two surviving sisters, surviving thanks to the fact that, under hypnosis, they had given up smoking five years earlier, a reprieve.

What the dead sister lacked in lifespan she had made up in comedic skills. The funeral in fact was a review of her career as a jokester, a prank, a perverse trouble-maker. Family stories were all of the same theme. This was the sister who, traveling with the other two, led her siblings into “situations.” Afterwards, she was the one who could remember the key details in an order that was effective for telling, if forgetful of actual sequence. Like all good comics, it was the story that mattered, and the specific quality of laughter that comes after a joke, even if it’s in a language you don’t understand.

So, the circled mourners were respectful but not at all despairing. But, as it took longer to get ready for the trip to the burial ground, they were becoming impatient. As it happened, a cat materialized (from a nearby trailer park, not at all unusual in this part of Virginia?) and took a shine to the sisters. It hopped in the car, and the agéd aunts, fond of cats generally, took a shine to it. I was assigned to clear the car, which I had to do fully five times, only to have the cat jump back in again. Where did this cat come from? And, why did it want to ride in the lead car with the sisters?

After repeatedly moving the insistent animal from the sisters’ back seat, it occurred to me that the only way to jail the cat was to put it into the chapel, where it might at least find some left-over communion wafers. When I did this, I turned from the deed to the crowd in the lot below, realizing that I was on the stage made by the entry steps and that I had just been tricked by the cat into delivering the Aunt’s Last Joke. I have heard stories told by “psychical” older friends who, having lost a spouse, receive a visit, most often from a bird but sometimes another animal, shortly after the funeral … a consolation visit, as if to say “I’m alright.” But, this visit was clearly improvised to fit the event at hand, to appeal to the largest audience possible. And, how was the “ghost-cat” to know that the parking lot would resemble an amphitheater?

The spectacle had fired up the funeral-goers so that, on our drive to the cemetery, cars passing in the other direction saw car after car behind the lead hearse filled with “mourners” laughing to the point of having tears roll down their cheeks. The next-most-droll sister remarked, “People probably think she was very rich.”

The White Goddess

This is a non-story with a portion that has to remain secret. Even the title borders on a violation of a contract I made with a now-dead geographer who taught at LSU, Milton Newton. Milton, in the 1980s a preview of the alt-right conservative we might catch on camera during the January 6 riot, was then a thoughtful reader of, among other philosophical materials, Alfred North Whitehead. He was a close friend my my advisor at the time, a native of Michigan who identified as a Southerner in the style of Richard Brautigan’s Confederate General from the Big Sur. I hadn’t noticed the streak of paranoia in my advisor, but Milton knew it well, and knew I was in danger of backlash, as those who dare to contradict are marked out, in the paranoid mind, for one of the thousand flavors of vengeful humiliation.

At a dinner at the advisor’s house, where humiliation was introduced at the stage only as an hors-d’œuvre, Milton designed to give me a preview of coming attractions with some examples from Whitehead that I didn’t understand. A good insult is one that everyone else but not the victim understands, and the advisor was a master craftsman at producing these. At a geographers’ annual meeting later that year, in New Orleans, Milton saw me in the mezzanine lobby of the conference hotel and called me over. Without any warning he asked me if I had read Kant’s third critique, and by chance I was able to say truthfully that I had. Well, Newton added, equally lacking any explanatory materials, that I should also get to know the White Goddess. I felt that perhaps Milton had learned the art of the insult from my advisor, and was humiliating me just for practice, since there was no one else around.

Newton’s reference to the White Goddess did not blip on my intellectual radar, which as yet knew nothing about Robert Graves’ famous book by that name, re-positioning history as a male take-over of maternal societies and religions. Instead, I had seen the White Goddess herself, in a dream about two weeks before the geography conference. I was with Ron Abler, a famous geographer in the US and department head at Penn State, in a “lookout box” that, I realized, anticipated the balcony where I had met Milton. From the box we looked onto a field below where a woman stood within a radiant halo of intense light. She was titanium white more than blond, transcendent, vibrantly beautiful. As with my dream of Borges’ Aleph, it had definitely taken place before hearing about the goddess from Milton Newton.

Newton’s reference to the White Goddess did not blip on my intellectual radar, which as yet knew nothing about Robert Graves’ famous book by that name, re-positioning history as a male take-over of maternal societies and religions. Instead, I had seen the White Goddess herself, in a dream about two weeks before the geography conference. I was with Ron Abler, a famous geographer in the US and department head at Penn State, in a “lookout box” that, I realized, anticipated the balcony where I had met Milton. From the box we looked onto a field below where a woman stood within a radiant halo of intense light. She was titanium white more than blond, transcendent, vibrantly beautiful. As with my dream of Borges’ Aleph, it had definitely taken place before hearing about the goddess from Milton Newton.

The long drive back from the conference was complicated by events that had happened on the drive down. My car had broken down north of Atlanta. I was saved by a kind couple, who somehow noticed that I was reading a copy of Wallace Stevens poems sitting in the shade of an overpass. Cellphones had not invaded the planet, so the nice couple drove me to a telephone, where I was able to reach my former (nice) advisor from Georgia State, who had, I knew, “connections” in the auto repair industry. Thinking to get only good advice, he volunteered to rent a hitch and rescue me, an act of kindness I never forgot. On the way back, I had to retrieve the repaired Saab 95, calling in more favors I hadn’t earned.

By the time I reached New York to meet up with my wife and her sister who lived on Sheridan Square at the time, I had driven through Richmond and thought to make a short tour of the town. The white marble buildings that populate the governmental center triggered a memory I had had in New Orleans. With the vividness of a déjà vu “recall,” every glint of sunlight, every turn of the road, presented itself as orchestrated. Stirred and shaken, I arrived in New York with the omen Milton had planted in my head, of finding the White Goddess. A person? A statue, as white as the buildings in Richmond?

By the time I reached New York to meet up with my wife and her sister who lived on Sheridan Square at the time, I had driven through Richmond and thought to make a short tour of the town. The white marble buildings that populate the governmental center triggered a memory I had had in New Orleans. With the vividness of a déjà vu “recall,” every glint of sunlight, every turn of the road, presented itself as orchestrated. Stirred and shaken, I arrived in New York with the omen Milton had planted in my head, of finding the White Goddess. A person? A statue, as white as the buildings in Richmond?

A book, it turned out. My wife’s sister’s apartment was on Sheridan Square, above the Ridiculous Theater where Charles Ludlum developed the high-camp genre of drama that  included such works as The Enchanted Pig, Mystery of Irma Vep, and Vampire Lesbians from Hell. Taking out the garbage one night to the laundry room on the ground floor, I discovered it was also the backstage for the tiny theater, and one of the two actors in the play was waiting for his cue, dressed in full Viking armor.

included such works as The Enchanted Pig, Mystery of Irma Vep, and Vampire Lesbians from Hell. Taking out the garbage one night to the laundry room on the ground floor, I discovered it was also the backstage for the tiny theater, and one of the two actors in the play was waiting for his cue, dressed in full Viking armor.

The morning after my late-night arrival, I went out for bagels at a nearby bakery while the sisters extended their coffee conversation. On the way back I took my reward for this involuntary kindness by stopping by the bookstore facing the square, a single long room generously funded by morning sunlight. The shelves had been spruced up for the day’s trade, but at the far end of the room there was one book out of place, the only book out of place. I walked to it, pulled it down, and without having to look at its cover, paid for it and left.

That’s all I can say.