With a shift towards psychoanalysis and the works of Jacques Lacan, the boundary language project turned to themes of anamorphosis, exitimity (inside-out conditions), discourse theory, and topology. This work has coalesced around a project of merging anamorphosis with extimity as “parallax domains” covering the full range of psychoanalysis but more easily accessed by popular culture, visual arts, cinema, architecture, and landscape. “Current Projects” means what is being pro-jected now, as a possibility. Sometimes it is no more than a structure or unexplained connection.

Struggling with Topology? Try Induction and Inversion Instead

Before you despair trying to understand what Lacan is doing in Seminars XIII and XIV to topologize the psyche, try the coupled operations of induction — the kind of puzzle whose chief example Lacan employs in his essay on Logical Time — and inversion, the idea Lacan embraces i the form of extimité, the inside-outness of the unconscious, which drives out suppressed thoughts on a highway of the Symbolic to the great outdoors. Inversion and induction are a new way of showing how Lacan’s interest in topology extended far beyond the conventionally assigned confines of the middle seminars. The real payoff of this insight is, however, the fact that inversion and induction are the logics by which cultures structure rituals practices, games, religious beliefs, myths, folktales and, later, the putatively more sophisticated products of the arts, literature, architecture, music, etc. We could even say that all objects, even those regarded as purely utilitarian, have an inner inversive/inductive economy. Wherever there is exchange and limit, inversion and induction are there to regulate the flows, the resistances, and the insulation that define the space and time of activities and transgressions.

Reading Seminar XIV: The Logic of Phantasy

With a few friends, this is one of those Lacanian seminars that is worth the trouble, since it addresses the question of the Imaginary’s role in the creation of the famous objet petit a, the object-cause of desire. Reading amounts to making commentaries on each Wednesday seminar (starting November 16, 1966) and ending June 21, 1967. Follow along with this link, but make sure to have the French text handy (it has better graphics than Cormac Gallagher’s English translation from audio transcripts.

Tower of Babel and the Question of Invisibility

Curiously, there is a double function in the “=” sign, one idea being that of identity, the other with “is easily confused with.” Both are potent in the polarity of invisibility and blindness, where the two are frequently identified and confused, as in the case of the Tower of Babel, architecture’s first major failed project. Assigned to span the interval between heaven and earth, the spiral form invites comparison with Lacan’s spiral of demand within a torus of desire, both implicating an idempotent middle term, jouissance, that advances the cause of desire, as a solenoid might a metal cylinder circled by a coil of wire, into a double circuit relationship. Is the top of the tower unfinished, ruined, or invisible? Or, does it successfully connect with the Empyrean, as was the case in its historical predecessor, the Babylonian-Sumerian ziggurat?

Curiously, there is a double function in the “=” sign, one idea being that of identity, the other with “is easily confused with.” Both are potent in the polarity of invisibility and blindness, where the two are frequently identified and confused, as in the case of the Tower of Babel, architecture’s first major failed project. Assigned to span the interval between heaven and earth, the spiral form invites comparison with Lacan’s spiral of demand within a torus of desire, both implicating an idempotent middle term, jouissance, that advances the cause of desire, as a solenoid might a metal cylinder circled by a coil of wire, into a double circuit relationship. Is the top of the tower unfinished, ruined, or invisible? Or, does it successfully connect with the Empyrean, as was the case in its historical predecessor, the Babylonian-Sumerian ziggurat?

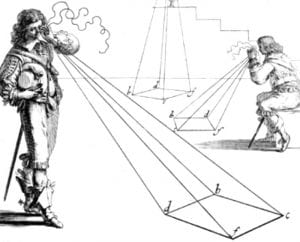

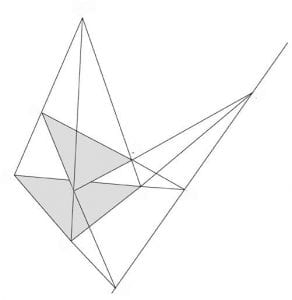

girard desargues’s theorem and the figure-ground

Girard Desargues (1591–1661) was a French mathematician who revived the theorems of Pappus of Alexandria (ca. 300 a.d.) to revolutionize the perspective drawing, among other things. He realized the potential of projective geometry and, in collaboration with Blaise Pascal, laid the foundation for a full edition version of a geometry that was logically prior to Euclid although it was discovered second. As when Lacan wondered what anamorphosis was before it was anamorphosis (my suggested answer: “the uncanny”), we might apply the same après coup logic to Euclid, with a sharper edge: “What was ‘geometry’ before it was ‘geometry’?” If projective geometry is the answer, it should be understood by adding, to the 19th century’s worth of rich development (Gauss, Riemann, Plucker, etc.), Desargues’ original interest in perspective. His main theorem involved the way two triangles fit within the cone of vision defined from a single viewing point would figure-ground each other. A visible triangle would perfectly eclipse any number of second triangles whose vertices touched the three lines radiating from the POV. The “figure triangle” would cast a perfect shadow over the “ground triangles.” No matter how these shadow triangles were positioned, lines drawn from the edges of the figure triangle and ground triangle would extend to intersect at three points all lying on a single line, an “eigenvector.” The consequence of visibility’s relation to invisibility is streamlined in this theorem. A “front” of a visible triangle presupposes a “back,” not just as the reverse side of a 3d planar figure but a pyramidal shadow able to contain multiple other triangles, all of which will have sides that extend to meet the eigenvector.

The twist involves seeing the shadow in terms of the ground of the “figure” or face of the visible triangle. The ground is the consequence of the figure, at the cost of being consigned to a “supportive role” at the perceptual and neural level. This would be a matter of a simple binary relationship without Desargues’ Theorem. The theorem’s eigenvalue focuses on the function of the cut between the front and back, the visible and the invisible, which makes of the face and its shadow (the perspectival relationship) a distinctive element (the eigenvector) that is a logical/structural consequence of visibility.

In an essay co-authored with Anahita Shadkam, we explored the ancient device, the “thaumatrope,” a Stone Age magic token used in preparation for the hunt, which was spun to “combine” images of the living animal and dead animal, capturing the “moment” of death that was both a part and not a part of the temporal continuum. The eigenvalue’s association with the spear as a vector is intriguing. In the story of Daphne and Apollo, Eros fashions a similar arrow, designed to infect Apollo with love and Daphne with hate. This arrow logic was repeated in the “surface of pain” (as Lacan calls it in Seminar VII, Ethics in Psychoanalysis) where Daphne runs across but cannot escape: a 2d self-intersecting, non-orientable projective topological form.

Returning to the case of the figure-ground promises to take advantage of Desargues’ “streamlined” experiment with perfectly eclipsed triangles, to show that any “face” involves this same kind of perfect eclipse. In other words, there is another side even when the surface is only 2d, another side that implicates the viewer as a vindictive criminal (like Eros).

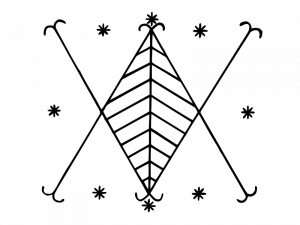

magic architecture

magic architecture

Clinical structures such as the “cosmograms” secretly inserted into the houses of masters in Colonial America intensified force-fields to enhance the effectiveness of curses (or blessing) murmured soto voce by Yoruba house-slaves. The connection between language and fluids allows us to consider Freud’s “energetics” doctrine (“Project for a Scientific Psychology,” 1895) afresh. When placebos and hypnosis’s power of suggestion are proven to be effective; when “mentalists” and close-up magicians can activate theatrical versions of the unconscious, it is time to put aside the bracketing of ethnographic magical practices as delusional or quaint. Into this mix add the devious “body loading” techniques of pick-pockets (the brief paralysis induced by repetitive

violations of personal space) to accept that magic is, if anything, about a virtuality of effectiveness operating within the more picturesque Euclidean perspectival virtuality. It is as if Desargues’ theorem about the perfectly eclipsed triangles found a quick way to summarize spatial magic through projective geometry.

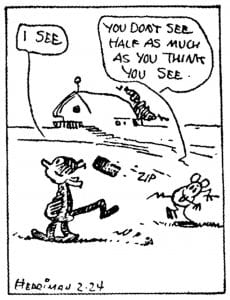

comics

[From the iPSA site]: It goes without saying that the advent of graphic novels was simply a formalization of the loose principle of popular culture’s ability to work as a collective unconscious, an “anxiety management machine” playing out, in the fictionalized lives of pathetic failures, animal totems, super-heroes, and timeless tricksters, a panel-by-panel freeze-frame version of psychoanalysis. Using evidence of Krazy Kat, cartoonists have merged their clever facility with the “inside frame” with cinematic sensibilities. Architecture theory has yet to treat this remarkable archive, but iPSA suggests that it should do so with Lacanian theoretics at hand.

sight is theft

The Looking Project is game designed for the Alethosphere, where the aim is to create a collective publication/website via files and edits exchanged by email. The subject is visibility/invisibility (Merleau- Ponty’s book of the same name comes to mind) but also the agent’s actions, looking at, staring, gazing, etc.

Method: Volunteer contributors (“beloveds,” les bien-amés) play any role, at any level, in return for credits listed in the web and paper publications. An axiom is that contributors benefit personally, for personal reasons that need not be standardized. Payback comes in the form of insights that can be used in one’s own work, accompanied by a guaranteed jouissance of writing.

Strategy: To cap the variety that, by definition, accrues to the subject of vision, visuality, visibility, etc., a tyrannical thesis is imposed: the relation of vision to theft, in particular the type of theft elaborated by Norman O. Brown in his book, Hermes the Thief. In many ways, Brown imposed a cap on the variety of functions attributed to the Greek/Roman god Hermes by supposing that, within the variety, there would be a single “logic” concerning boundaries and their violation.